I download fansubs every now and then, so I got some stake in this argument. However, I am interested in buying DVDs. My policy is to delete files once I have watched them, but here's something I would say: the big problem is that people like me cannot afford the premium at which most anime series are sold.

Anime series tend to market at above the cost of a typical DVD, and in what I think is really a hangover from the days of VHS distribution, are split between a number of different, separate DVDs. Contrast this with the way most DVDs of traditional series are sold in America: that is, season by season. It's an inefficient business model, especially when the long term arcs of the series are of great interest to the consumer. Some would say you want consumers to jump through hoops, but the real problem with that is that the hoops are seen as unnecessary, and you have a difficult to control, and much easier alternative on the side.

So what to do?

The best way to do this, I think, is to do what music producers did not do until it was too late: provide a nice, safe legal means for people to do what they do now.

And what do fansubs do? Quick and dirty distribution of high quality anime, within days of broadcast, free of charge. Is this impossible for the corporations in Japan? It's not for the fansubbers. These people, for the love of it, get these things done in hours. I have complete faith that folks who get paid to do this could very easily repeat such feats.

Even if the delay were more like a week, I think something still could be managed. The key here is to understand the paradigm by which both movie and music distribution became online-free-for-alls.

Ask yourself: what is it here that these online means of distribution resemble, aside from the on-demand feature? Radio and Television. Tune in, and depending on whether people pay a premium or not, they can see all kinds of different movies and television shows with no out of pocket cost beyond a monthly bill.

The one big barrier, it seems, to doing all this in a timely manner, is not translation, but dubbing. The need to dub each and every show before it hits our shores is a huge part of both the overhead and the delay in getting this product to these shores. Is dubbing necessary, at least at that stage?

No. It's a nice thing to have, for many people, but the explosive growth of fansubbing demonstrates that it is not necessary to folks for their enjoyment. To get their anime now, in plentiful supply, and follow the stories in progress, people are willing to read the translation at the bottom of the screen. Observing the history of Anime in America, we can see that visuals and story are the primary draws here, not the English language. The conventional wisdom is that people will not go to see a movie drenched in subtitles. Yet people go to see movies like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, The Passion of The Christ, Kung Fu Hustle, and many others like them, with little complaint. Heck, the second of the two is written in a couple of dead languages, and the audience didn't seem to mind!

It might be a minus if you're marketing crap, but then that's your fault.

People don't need perfect translations or English dubs to want to seek out and enjoy anime on a near real time basis. Give them a subtitled translation, and they'll watch.

So what am I suggesting?

Two routes of distribution present themselves, so long as the people are willing to do things a little quick and dirty: Digital TV and Streaming Internet distribution, with both premium channel models that remove commercials, and basic channel models that include American commercials from American sponsors.

DVDs can then become what they are for most American shows: a way to milk the cow for those who truly do like what they see. The dubs for these shows can be come a part of the premium package of documentaries and other extras that DVDs are beloved for. You either end up justifying the higher price by making it a premium item, or by giving yourself the kind of volume through your primary broadcasts and webcasts that allows you to price them lower and still reap a profit.

The thing to keep in mind is that recorded mediums have always been premium items. Unfortunately, recorded mediums and distributive mediums are no longer as different in real terms. In certain markets, this used to provide a kind of premium priceability to the market- you either get it here, or nowhere else. The reality of today's market, is that people are now capable, either through legitimate means or not, of bypassing this.

Sooner or later, we have to face the globalizing consequences of digital convergence. You have to realize that you have a product that people want, and your main business model can no longer depend on any ability to keep it from them. Like Luke Skywalker says to Jabba the Hutt in Return of the Jedi, you can either profit from this, or be destroyed.

Profit from people's immediate desire for this product, then profit from their wish to have a deluxe version of the shows they really liked. Indeed, you can measure the ratings that shows get to find where the market's heading.

In the end, the only way to get past fansubbing, is to become the fansubbers yourself, and make it a workable commercial model. That is what I am suggesting here.

Saturday, December 15, 2007

Friday, December 14, 2007

A Small Enviromental Idea

I think it would be in our best interests as a nation to make recycling a priority. I know, it sounds cheesy, but when you really think about it, we're chucking a hell of a lot of resources, including petrochemicals, plastics, paper, metal, and other items which we will then have to replace by pumping up some oil, mining some metal, or doing some other kind of work.

I know, also a bit of a cliche. But when you take a trip out to the local landfill, drive up a small mountain of former landfill to get the current part, and it is itself quite immense, you just have to think about just how much of our resources end up lost to us in a place like this.

We might end up, at some point in the future, using the wonders of nanotechnology to pick through what we once considered disposable. How much of our own garbage do we want to be picking through, and how soon?

I know, also a bit of a cliche. But when you take a trip out to the local landfill, drive up a small mountain of former landfill to get the current part, and it is itself quite immense, you just have to think about just how much of our resources end up lost to us in a place like this.

We might end up, at some point in the future, using the wonders of nanotechnology to pick through what we once considered disposable. How much of our own garbage do we want to be picking through, and how soon?

Monday, October 01, 2007

Digital photography and Body Consciousness

I recently discovered some things about the way programs like Adobe Photoshop can be used to alter the way a person looks, and I think we should consider the implications of these facts in determining our expectations of our own bodies.

Men and women both stare at photos in magazines and lament that they can't have the perfect bodies they see there. What some of them may not realize is the extent to which these photos might be touched up. Heavily. Blemishes can be removed with the touch of a button, inconvenient curves distorted and erased, shadows and highlights reworked to add definition to muscles, perfection to skin. Blurring techniques can clear up complection, and even eyes can be moved about, if need be, to get that perfect look.

In the age of Photoshop, it's worth considering that almost no photography done professionally comes out in a national publication without extensive retouching.

Especially when it comes to being thin. As if the mounds of exercise, skimpy diets or other methods are not enough, those retouching glamour shots often use the tools to smooth away the places where the flesh bunches up where it shouldn't.

In short, we're making our assumptions about what thin looks like based on a digital fiction.

Here's a simple point to be made: the camera always lies. With Photoshop, and other image editing programs, it makes it even better at lying.

So what are we to do, raid the downtown headquarters of the modeling agencies, burn it to the ground? No. We have to change our attitudes about what these images mean. With documentary photography, of course, we should not accept much more than a few technical fixes for clarity. But beyond that, we should keep this one important point in mind: these are forms of communication, not necessarily representations of the truth.

The models in these shots do plenty of work to get their bodies in shape. They probably take up their whole lives in this. Rare ones can get away with doing little exercise and still eat like a normal person, but for the most part, this is a job. Even so, it's revealing that even as they best approximate our ideas of perfection, these people still must be retouched and reshaped in order to meet that ideal.

So let's get clear on this: the people commissioning and taking these shots are not representing reality, they are communicating something to you, something the models, the photographer, the program and the digital artist come together to shape. They are distilling something that in reality would be far more mundane, if it weren't for the labor of all involved.

The inspiration for this post came from working on exercises in Photoshop Restoraton and Retouching, by Katrin Eismann. If you want to know just how much the photos we see are communication, and not reality, this is the book to teach you.

Men and women both stare at photos in magazines and lament that they can't have the perfect bodies they see there. What some of them may not realize is the extent to which these photos might be touched up. Heavily. Blemishes can be removed with the touch of a button, inconvenient curves distorted and erased, shadows and highlights reworked to add definition to muscles, perfection to skin. Blurring techniques can clear up complection, and even eyes can be moved about, if need be, to get that perfect look.

In the age of Photoshop, it's worth considering that almost no photography done professionally comes out in a national publication without extensive retouching.

Especially when it comes to being thin. As if the mounds of exercise, skimpy diets or other methods are not enough, those retouching glamour shots often use the tools to smooth away the places where the flesh bunches up where it shouldn't.

In short, we're making our assumptions about what thin looks like based on a digital fiction.

Here's a simple point to be made: the camera always lies. With Photoshop, and other image editing programs, it makes it even better at lying.

So what are we to do, raid the downtown headquarters of the modeling agencies, burn it to the ground? No. We have to change our attitudes about what these images mean. With documentary photography, of course, we should not accept much more than a few technical fixes for clarity. But beyond that, we should keep this one important point in mind: these are forms of communication, not necessarily representations of the truth.

The models in these shots do plenty of work to get their bodies in shape. They probably take up their whole lives in this. Rare ones can get away with doing little exercise and still eat like a normal person, but for the most part, this is a job. Even so, it's revealing that even as they best approximate our ideas of perfection, these people still must be retouched and reshaped in order to meet that ideal.

So let's get clear on this: the people commissioning and taking these shots are not representing reality, they are communicating something to you, something the models, the photographer, the program and the digital artist come together to shape. They are distilling something that in reality would be far more mundane, if it weren't for the labor of all involved.

The inspiration for this post came from working on exercises in Photoshop Restoraton and Retouching, by Katrin Eismann. If you want to know just how much the photos we see are communication, and not reality, this is the book to teach you.

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

Why I have always liked Harry Potter, Despite What the Snobs Say...

I have the good fortune of being one of the original readers of Harry Potter. As a science fiction and fantasy fan, I was on the look out for new authors, new works, and Potter fit in nicely. I don't remember how long the book spent on my shelf, but I remember picking it up when I first saw it at the Baylor Bookstore.

My reaction to the first book was that I wanted more. But before I go on, let me recall that her audience hasn't exactly been bereft of material to read in this genre. There have been plenty of predecessor series. There's the Prydain Series by Lloyd Alexander, featuring our favorite Assistant Pig Keeper. There's The Dark is Rising sequence by Susan Cooper, which featured a fine cast of characters, including Will Stanton, young man, yet one of the Old ones, and Bran, the strange Welsh kid with the surprising family connections. There's The Chronicles of Narnia, which recently got its own cinematic treatment. There are likely quite a few more, but my recollection escapes me, and I don't want to belabor the point too much. Others might undoubtedly recall others, and I'd be happy to hear about them.

And lets not forget Grimm's Fairy Tales, Hans Christian Anderson's work, and a multitude of others. Children's fantasy is a rich literary tradition.

Which may be part of the problem. Many works scorned in their day are grandfathered into later canons of literary greatness by readers with fond memories and nobody still alive to drop it in the waste basket as trash. Harry Potter has the problem that its, well...

New. Test of time, and what have you.

Maybe Potter will end up as a curiosity of our times, remembered mainly by enthusiasts and lovers of esoterica. But lets not forget, that a lot of people wrote in the old days for the same purpose they write today: Money, and because they love doing it.

Rowlingly obviously loves doing this. Her exquisite sense of detail would allow no other conclusion. She gave the cinematic translators of her work a magnificent headstart. Her plots are well organized, the dialogue fairly good. She takes care with how she reveals information, and the mysteries that form the heart of her novels are well organized. As for money, well she's getting a sh... well, a lot of it.

Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, Charles Dickens, and many others wrote not for the future idolization of their art, but for the love and the profit of it. I know that's kind of a generalization, but if you look into the history of many of the authors of what we call canon, you'll find more than a few commercial works, more than few overripe works of popular fiction.

I will not say that Harry Potter Books will necessarily become literature in the years to come. That truly is beyond my ability to say. But I will say this: It's popular enough to have some staying power, on the basis of having soaked into to enough homes and libraries, and it's of good enough quality to ensure that folks who pick it up, whether it remains out and about or gathering dust on some distant shelf, will pick it up and read it. So it could join works like Robinson Crusoe, The Three Musketeers, Great Expectations and others on the lists.

But what's the deal with the lists anyways? I'm going to tell you a little secret here: The lists are an accident! There are plenty of works we could speak of that would not have gotten on them had the folks who determine canonicity now been in charge. I look at a lot of what people read as literature, and some of the work is genuinely good, some of it not. Today's literary elites focus so much on pushing a certain world view, a certain view of realism, surrealism, postmodernism, or whatever camp they lump themselves into, that they're missing the new canon of literature as it rolls by them. They'll pick up on something that resembles their world view, like Pullman's His Dark Materials, but they'll miss a great deal of the other stuff, because it doesn't fit their idea of what is worthy.

Now my brother's much further into the modern works that I am, or care to be, but I notice that often enough he picks works that have a sense of humor, rather than loading himself up with only depressing material. I can imagine that there's no accounting for taste, which is why all kinds of books enjoy success, but still, there are some observations I'd like to make.

Genre work, meaning the stuff that doesn't stick to absolute reality, has a bad rap. That said, There's artistry in creating new worlds, or at least in doing some refit to this one. We can see in the works of Salman Rushdie and others this kind of approach. Whether you call it magical realism, fabulism or whatever, popular authors of the literary canon often drop in for a visit to fantasy and sci-fi land. And why not?

People right stories to figure out what you could call the human condition. But just consider all the things that go into that- our civilization, our culture, our sensibilities. There's a lot of space in there for examination of things like our relationship to technology, to religion, to all kinds of things. Fantasy and sci-fi, world-building works in particular, have their own territory to explore, their own intuitive truth to uncover.

While the genres can be escapist, they can also act as kind of a strange loop, as Douglas Hofstadter would call it, whereby readers can escape to the other worlds and parallel dimensions, and nevertheless come back deepened for their frivolity, because they come back to know the place they are in for the first time. That's perhaps one of the things cultural elitists hate- that they lose the control of those minds, that these works so entrance readers as to take them away from what's real.

But what is real? As a political writer on Watchblog, I've noticed what can only be called a strong divergence between what different parties consider real. Its noticeable elsewhere. Now I am not a big fan of philosophies that say that there is no objective reality, only what is brought into existence by consensus of belief. I believe there is an objective reality, but that we all have subjective, incomplete understandings and perceptions of it. Reality as it exists may be objective, but reality as we perceive it is a different story. With all that in mind, though, it's still important to seek the best possible understanding of that objective reality, to go beyond the shell of our perceptions, the necessary illusions that they are.

Fantasy and Science fiction allow us to look at the way people think and deal with cultures without necessarily having to glance directly at our own.

There are magnificent reflections of human truths in Harry Potter, and I believe that this is part of its lasting appeal. The relationship between Dumbledore and Potter, Potter's development into adolescence, the petty rivalries and lifelong grudges of personal and professional life, carry into her books.

They, among other aspects of a narrative work, literary or otherwise, contribute to what could be called the experiential value of the work.

The processes of the human mind are complex, multifacet, and represent the difference between what one is told, what one is shown, and what one experiences. Art is about taking advantage of the methods by which we seek to understand the world as reality, and using it to communicate wisdom and knowledge about the world too complex or beyond the person's normal experience to understand. It is also about how we train our minds to deal with the world around us.

Harry Potter's world is complex enough to believe in, with characters that are complicated enough to play around believeably in this world as human beings, and not just ciphers for the author's feelings. In all our self-indulgence, we writers have a tendency sometimes to put our own feelings as greater than our readers, but the truth is, no matter what we do, the success of our work depends on how we engage our readers, and how well we do it. Some would like to fantasize about how they will draw in an audience, or how they should be drawing in the audience instead of some author who just got lucky (from their point of view), but the fact is, by entering the profession they have, they've put the fate of their stories from the get-go, and have to do that to make art or to make money.

So my advice to those who hate what Potter has done to literature is this: compete. Be dazzling storytellers. Be original. Don't be a cliche, regardless of whether you're literary or commercial in your inclinations. Have some fun, while you take the work seriously. Understand that without the audience, without the bridge you build to them in your words, your work, your imaginings are incomplete. Only when somebody puts down a book satisfied, having had a worthy experience, can the art and the commerce of your work be complete.

My reaction to the first book was that I wanted more. But before I go on, let me recall that her audience hasn't exactly been bereft of material to read in this genre. There have been plenty of predecessor series. There's the Prydain Series by Lloyd Alexander, featuring our favorite Assistant Pig Keeper. There's The Dark is Rising sequence by Susan Cooper, which featured a fine cast of characters, including Will Stanton, young man, yet one of the Old ones, and Bran, the strange Welsh kid with the surprising family connections. There's The Chronicles of Narnia, which recently got its own cinematic treatment. There are likely quite a few more, but my recollection escapes me, and I don't want to belabor the point too much. Others might undoubtedly recall others, and I'd be happy to hear about them.

And lets not forget Grimm's Fairy Tales, Hans Christian Anderson's work, and a multitude of others. Children's fantasy is a rich literary tradition.

Which may be part of the problem. Many works scorned in their day are grandfathered into later canons of literary greatness by readers with fond memories and nobody still alive to drop it in the waste basket as trash. Harry Potter has the problem that its, well...

New. Test of time, and what have you.

Maybe Potter will end up as a curiosity of our times, remembered mainly by enthusiasts and lovers of esoterica. But lets not forget, that a lot of people wrote in the old days for the same purpose they write today: Money, and because they love doing it.

Rowlingly obviously loves doing this. Her exquisite sense of detail would allow no other conclusion. She gave the cinematic translators of her work a magnificent headstart. Her plots are well organized, the dialogue fairly good. She takes care with how she reveals information, and the mysteries that form the heart of her novels are well organized. As for money, well she's getting a sh... well, a lot of it.

Alexandre Dumas, Victor Hugo, Charles Dickens, and many others wrote not for the future idolization of their art, but for the love and the profit of it. I know that's kind of a generalization, but if you look into the history of many of the authors of what we call canon, you'll find more than a few commercial works, more than few overripe works of popular fiction.

I will not say that Harry Potter Books will necessarily become literature in the years to come. That truly is beyond my ability to say. But I will say this: It's popular enough to have some staying power, on the basis of having soaked into to enough homes and libraries, and it's of good enough quality to ensure that folks who pick it up, whether it remains out and about or gathering dust on some distant shelf, will pick it up and read it. So it could join works like Robinson Crusoe, The Three Musketeers, Great Expectations and others on the lists.

But what's the deal with the lists anyways? I'm going to tell you a little secret here: The lists are an accident! There are plenty of works we could speak of that would not have gotten on them had the folks who determine canonicity now been in charge. I look at a lot of what people read as literature, and some of the work is genuinely good, some of it not. Today's literary elites focus so much on pushing a certain world view, a certain view of realism, surrealism, postmodernism, or whatever camp they lump themselves into, that they're missing the new canon of literature as it rolls by them. They'll pick up on something that resembles their world view, like Pullman's His Dark Materials, but they'll miss a great deal of the other stuff, because it doesn't fit their idea of what is worthy.

Now my brother's much further into the modern works that I am, or care to be, but I notice that often enough he picks works that have a sense of humor, rather than loading himself up with only depressing material. I can imagine that there's no accounting for taste, which is why all kinds of books enjoy success, but still, there are some observations I'd like to make.

Genre work, meaning the stuff that doesn't stick to absolute reality, has a bad rap. That said, There's artistry in creating new worlds, or at least in doing some refit to this one. We can see in the works of Salman Rushdie and others this kind of approach. Whether you call it magical realism, fabulism or whatever, popular authors of the literary canon often drop in for a visit to fantasy and sci-fi land. And why not?

People right stories to figure out what you could call the human condition. But just consider all the things that go into that- our civilization, our culture, our sensibilities. There's a lot of space in there for examination of things like our relationship to technology, to religion, to all kinds of things. Fantasy and sci-fi, world-building works in particular, have their own territory to explore, their own intuitive truth to uncover.

While the genres can be escapist, they can also act as kind of a strange loop, as Douglas Hofstadter would call it, whereby readers can escape to the other worlds and parallel dimensions, and nevertheless come back deepened for their frivolity, because they come back to know the place they are in for the first time. That's perhaps one of the things cultural elitists hate- that they lose the control of those minds, that these works so entrance readers as to take them away from what's real.

But what is real? As a political writer on Watchblog, I've noticed what can only be called a strong divergence between what different parties consider real. Its noticeable elsewhere. Now I am not a big fan of philosophies that say that there is no objective reality, only what is brought into existence by consensus of belief. I believe there is an objective reality, but that we all have subjective, incomplete understandings and perceptions of it. Reality as it exists may be objective, but reality as we perceive it is a different story. With all that in mind, though, it's still important to seek the best possible understanding of that objective reality, to go beyond the shell of our perceptions, the necessary illusions that they are.

Fantasy and Science fiction allow us to look at the way people think and deal with cultures without necessarily having to glance directly at our own.

There are magnificent reflections of human truths in Harry Potter, and I believe that this is part of its lasting appeal. The relationship between Dumbledore and Potter, Potter's development into adolescence, the petty rivalries and lifelong grudges of personal and professional life, carry into her books.

They, among other aspects of a narrative work, literary or otherwise, contribute to what could be called the experiential value of the work.

The processes of the human mind are complex, multifacet, and represent the difference between what one is told, what one is shown, and what one experiences. Art is about taking advantage of the methods by which we seek to understand the world as reality, and using it to communicate wisdom and knowledge about the world too complex or beyond the person's normal experience to understand. It is also about how we train our minds to deal with the world around us.

Harry Potter's world is complex enough to believe in, with characters that are complicated enough to play around believeably in this world as human beings, and not just ciphers for the author's feelings. In all our self-indulgence, we writers have a tendency sometimes to put our own feelings as greater than our readers, but the truth is, no matter what we do, the success of our work depends on how we engage our readers, and how well we do it. Some would like to fantasize about how they will draw in an audience, or how they should be drawing in the audience instead of some author who just got lucky (from their point of view), but the fact is, by entering the profession they have, they've put the fate of their stories from the get-go, and have to do that to make art or to make money.

So my advice to those who hate what Potter has done to literature is this: compete. Be dazzling storytellers. Be original. Don't be a cliche, regardless of whether you're literary or commercial in your inclinations. Have some fun, while you take the work seriously. Understand that without the audience, without the bridge you build to them in your words, your work, your imaginings are incomplete. Only when somebody puts down a book satisfied, having had a worthy experience, can the art and the commerce of your work be complete.

Sunday, April 01, 2007

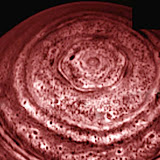

Hexagon on Saturn?

I think I have a rough idea of what this atmospheric formation on Saturn might mean.

Water spun very fast in a bucket will take on hexagonal shape. The speed has a lot to do with things, and Saturn's winds are damn fast, over a thousand miles an hour.

|

| hexagon |

Water spun very fast in a bucket will take on hexagonal shape. The speed has a lot to do with things, and Saturn's winds are damn fast, over a thousand miles an hour.

Wednesday, January 17, 2007

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)